I first saw the famous painting of Ophelia on Substack, of all places. Someone made a note calling it “their favorite painting of all time,” and funnily enough, I just scrolled right past it. I never thought about it again until maybe a week later—the image just popped into my head at random. And it stuck this time around. After a frantic Google search of “dead girl floating in paradise painting,” it was found. My muse.

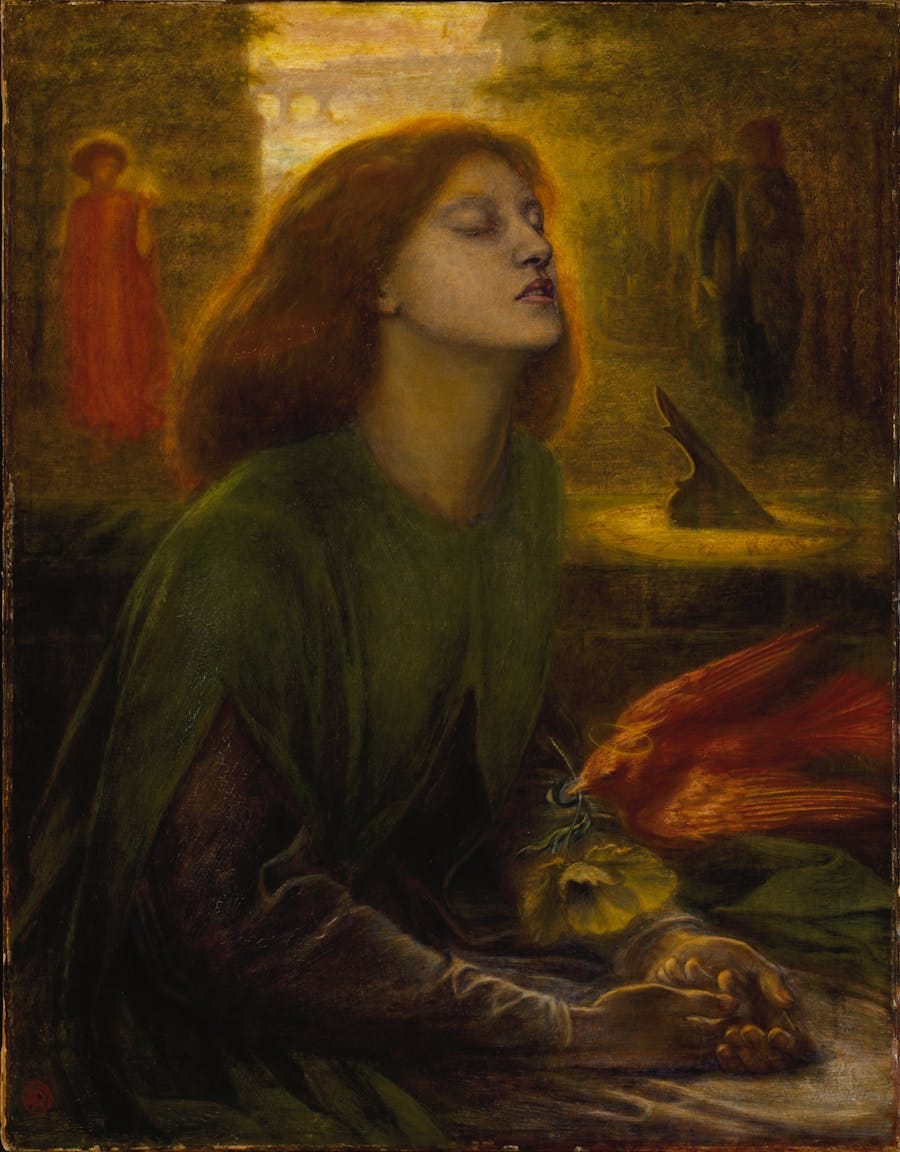

Ophelia by John Everett Millais, depicting Ophelia’s final moments from Act IV, Scene VII of Shakespeare’s Hamlet, was a product of the Pre-Raphaelite movement and a transformative painting of its time. Millais uses seemingly perverse techniques, such as symbolism of death, unidealized depiction of the subject, and focus on realistic landscapes, rather than the accepted Italian painting style that shows subjects in a perfect light. These choices subvert Victorian-era standards of femininity that overly emphasize demureness and create a complex, haunting portrayal of Ophelia, illustrating her descent into madness in a way that evokes a sense of unconventional beauty. Understanding the time period is essential for understanding the impact of the piece. But first, we need to answer the questions: Why Millais? And why Ophelia?

what is art, anyways?

There are many definitions of art, of course. Some may even argue that such an abstract yet physical articulation of the human soul, eternally integrated into our consciousness, shouldn’t need a definition. If you go out on the street and ask 10 random people, most likely, all 10 people are going to tell you something different. Many might say, simply, the inner thoughts of an artist. Another might answer, what the viewer makes of the piece. (And that’s an interesting question for later—who defines what art is?) It’s always something very personal, a meaning strung together through the conjunction of all art exposed to or experienced by the person. Yet, there are similarities to each definition—because chances are we’ve all seen some of the same pieces of art in passing. Similar elements are: storytelling, aesthetics, entertainment, medium, revolution, and change. Art has shown up throughout the course of history, every time with a slightly different purpose, yet united at their core is expression.

Anyways, here’s my definition, trying to incorporate all the similar elements: Art, at its core, is a medium for an artist to convey their unique ideas or beliefs as a story perceptible to a viewer. Though it is often sought after by the viewer for its aesthetics, an artist sees it principally as a language, using it to convey their own opinions on concepts such as beauty by drawing subjects through their own eyes, which can counter current cultural and artistic norms. Emphasis on the last part for this piece. Of course, not all art has to have a purpose, but Ophelia seems like it was painted with a goal, even if in the back of the artist’s mind.

the brotherhood

The Pre-Raphaelite movement, created in 1848 in England, was founded by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Everett Millais, and William Holman Hunt, and was a response to the rapid industrialization of England during the Victorian era and the unimaginative, Raphael-inspired style adopted by the Royal Academy of Art at that time. Their paintings were characterized by colorful scenes often found in religion or literature, which were depicted in unrelenting realism inspired by Pre-Raphael and medieval art. Many of the artists painted women, often their wives and sisters. Ophelia is one of the most recognizable and characteristic paintings of this movement, but there are so many more. Many of their works faced backlash from other celebrated artists and authors at the time for being “ugly.”

le shakespeare

A frequently discussed question in Hamlet: Did Ophelia commit suicide? Well, in the scene depicted, Act IV, Scene VII, Ophelia, heartbroken and mad, falls into a lake and drowns. Gertrude, the queen, later recalls her death, saying

“But long it could not be

Till that her garments, heavy with their drink,

Pulled the poor wretch from her melodious lay

To muddy death.”- Hamlet 4.7.205-208

In Gertrude’s speech describing Ophelia’s death, the reader will notice that it is a retelling, and Gertrude did not see first-hand what had happened. This repeats a theme throughout the book that has other characters constantly pushing their ideologies on her words to take advantage of her, and this may be associated with Gertrude twisting her death to be more ambiguous—it is unclear if she drowned purposefully or accidentally. Nevertheless, Millais, like every other viewer, had his own interpretation. He depicts Ophelia as serene, not struggling, showing his Ophelia either purposefully falling in or accidentally slipping, yet not resisting the hands of death. This painting demonstrates how Millais reinterprets Shakespeare’s text to give power back to Ophelia, showing that she may have embraced death herself—an uncommon topic in the Victorian era. Through his depiction, we can see that art was his outlet to modify the text in a way that, while still being faithful, reflected his more radical point of view on femininity and death.

The theme of death is further changed by the flowers shown in the painting. Hamlet mentions Ophelia making flower garlands with “crow-flowers, nettles, daisies, and long purples.” Millais chooses to include these flowers floating alongside Ophelia’s body, possibly to represent her social constraints and romantic history with Hamlet that ultimately led to her demise. Crow-flowers symbolize naivety and ingratitude; nettles, both protection and punishment; daisies, purity; and “long purples” (which don’t exist but are purple loosestrife in the painting), resilience.

However, Millais also includes symbols not shown in the book, notably a red rose that symbolizes love, along with a weeping willow branch overhead. This artistic choice could have been pointing at the love that caused her to become mad, as well as romanticizing her death as something beautiful. The symbolism and selective taking of elements from the text transform Ophelia’s death into a romantic narrative different from other interpretations, giving the adaptation a personal lens through Millais’s eyes.

victoria’s secret-level beauty standards

Ophelia’s portrayal in the painting, including her expressions, also deviated from the typical expressions of a forlorn maiden. In the late 18th and 19th centuries, “madness” was often associated with women. There were increasing proportions of women in asylums, and Victorian psychiatry diagnosed many more women than men with mental illnesses. Madmen were more aggressive, while madwomen: sexually provocative, self-injuring spectacles. Oftentimes, these “madwomen” were depicted with melancholy and isolation, reinforcing the cultural norms at the time that associated women with fragility. At the same time, the Industrial Revolution sparked an increase in gender roles, as men were off to work and women were more associated with household chores. Along with this? Stereotypes. Hope Werness, an art historian, describes this theme, prevalent all throughout the 19th century, as the “modest maiden.” The associated characteristics: idealized femininity and innocence.

During this time, Ophelia as a character emerged as a popular muse to counter this pattern. Instead of passiveness like similar muses Maria from Sentimental Journey and Crazy Kate from The Task, who were positioned in a state of contemplation and aimlessness, Ophelia was often depicted with vigor, intrusion, and unruliness—after the Shakespearean text. However, Millais’s Ophelia differs from both traditions. Ophelia was often depicted in groups, rarely solo. However, Millais, being interested in the character, took the opportunity to render her and her alone. Because the scene gives way for her vulnerability in the face of death, her figure is rendered with ambiguity: her hands up, as if embracing death, but her face passive. Her eyes are open, and her mouth is slightly parted, which can be interpreted as a mix between surrender and pleasure. The pleasure aspect is typically unheard of in paintings of “maidens,” especially when the woman is dying (possibly by suicide), as it was seen as too much of a deviation from the ideal characteristics, such as helplessness.

Furthermore, through their model choices, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood challenged the beauty standards of women at the time. To many authors, including Charles Dickens, “inconsistent” and “unconventional” features were often associated with disgust or hate, with homogeneity being valued the most. He even went on to criticise Millais’s other work for being ugly. Elizabeth Siddal, Millais’s model for this painting, had a loose dress, full lips, and loose, bright red hair, and Ophelia’s appearance in the painting exudes boldness, directly contradicting the “modest maiden” and melancholy madness in a more direct, visual way.

mother earth above all

John Everett Millais, like other Pre-Raphaelite painters, also put emphasis on depicting nature, no matter how unkempt it was. In one of Millais’s own letters to a supporter in 1850 (later published in an anthology by his son), he describes his process:

“You will see that I am writing this from Kingston… I sit tailor-fashion under an umbrella throwing a shadow scarcely larger than a halfpenny for eleven hours… I am threatened with a notice to appear before a magistrate for trespassing in a field and destroying the hay; likewise by the admission of a bull in the same field after the said hay be cut; am also in danger of being blown by the wind into the water, and becoming intimate with the feelings of Ophelia when that lady sank to muddy death, together with the (less likely) total disappearance, through the voracity of the flies.”

This shows his sheer determination in finding and using the perfect spot for the backdrop, despite the discomfort and inconveniences. In the painting, we can see all this greenery by the river that he describes, preserved in great detail. Shades of brown mix with the greenery around Ophelia’s body, grounding her spirit in an almost hyperrealistic natural garden. By replicating the flora in a truthful manner, Millais used his background in realism to further defy the idealized standards of his day.

Later, in another letter in 1851 to the same supporter, Millais describes the flowers, writing that:

“The flowering rush grows most luxuriantly along the banks of the river here, and I shall paint it in the picture. The other plant named I am not sufficiently learned in flowers to know. There is the dog-rose, river-daisy, forget-me-not, and a kind of soft, straw-coloured blossom also growing on the bank.”

Wow, what a naturalist. Even though these flowers were not mentioned in the play, Millais was adamant about preserving the natural beauty of the river and painted the riparian greenery in its full glory. Because he was able to recognize all the different types of flowers, we can infer that he’s done a lot of research and spent a lot of time observing nature in preparation for his paintings. His attention to the surroundings of Ophelia’s resting place, despite not being explicitly described in the play, is a paradigm for Pre-Raphaelite values and commitment to nature.

wait… people actually hate this painting?

The critical reception for this painting was… mixed. The negative reviews just show how many people at the time did not see value in the honest, unidealized depiction. Notably, a critic from The Times described the setting as an ugly “weedy ditch.”

The same critic in the newspaper went on to criticize other works of the movement for their “unattractiveness” as well, suggesting that the Brotherhood’s deviation from the perfect Royal Academy of Art standards was just so distasteful. When they’re praising another painter, William Maclise, they write:

“Not far remote from this production of an experienced painter like Mr. Maclise must be placed the more crude and grotesque illuminations of Mr. Millais and his friends.”

- Review in The Times, May 1852

(What a menace… God forbid someone bring a unique idea.) This further emphasizes the distinction between the two Victorian-era art styles in not only the beauty standards of women, but also of nature. Even though the background is far from idyllic, Millais purposefully chooses this setting to elevate the “ditch” Shakespeare describes into something reflective of Ophelia’s unraveling mental state, adding to the symbolic meaning of the painting and simultaneously expressing how he, as an artist, truthfully feels the scene should be expressed.

If we view Ophelia now, at first glance, we might see just another basic, pretty Renaissance painting of a helpless girl drowning. However, we can only then truly appreciate the boldness and unconventionality of John Everett Millais, as well as the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, for their time, if we delve deeper into the context behind this painting. The popular style spread throughout England then, contributing to the gradual shift from a monotonous depiction of female subjects and nature to a more diverse, natural portrayal, leaving behind a legacy of iconic paintings that outlive themselves (and most definitely outlive their critics).

p.s. man, art is so cool. if you made it this far, thanks for reading! hope it was interesting :) wrote this for english class, tried to make it a bit more conversational for substack. i actually had quite a bit of a journey trying to find stuff—i had to de-javascript-ize the times website just to find the critic’s og review because the 1852 issue was behind a paywall and i didn’t know if wikipedia could be trusted. also shoutout to like 17 jstor articles and 12ft ladder and my school computer for getting me through.